The Airborne Invasion of Southern France

Operation Dragoon

Our generation, which was the first to employ parachute and glider borne troops in armed combat against an enemy force, should refuse to accept revisionist changes in the description or accounts of the deployment of these forces and their subsequent operations should they differ from what we actually experienced.

If we are not vigilant in the preservation of the history of our actions, then subsequent generations of historians might try to color the facts with their own differing interpretation of who we were and what we did. This account of OPERATION DRAGOON will, for the most part, deal with official After Action Reports written by airborne units, and their higher echelons of command, that were directly involved in the planning and conduct of OPERATION DRAGOON.

This historical account will primarily present the big picture aspects of OPERATION DRAGOON. Most Airborne and Troop Carrier units that participated in this operation have already published their own individual unit histories which include their specific roles and actions. What is presented here will compliment these unit histories. When specific Unit Reports are used they are intended to fill out and amplify the broader aspects of OPERATION DRAGOON.

The initial concept and planning of OPERATION DRAGOON was shrouded in controversy beginning as far back as 1943. It was during the QUADRANT conference, held in Quebec during August 14-24, 1943, that both President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill, their advisors, and the Combined Chiefs of Staff, decided on a target date for OPERATION OVERLORD, the invasion of Normandy. The date for OVERLORD was initially set for May 1, 1944. At this same time, the invasion of Southern France was decided on and the code name of ANVIL was assigned to the operation.

Prime Minister Churchill, even at this very early date, voiced his concern over the selection of the Southern France approach and strongly championed a military inroad into the Balkans. Churchill resisted ANVIL (the code name later changed to DRAGOON) right up until August 9, 1944, only six days before the actual invasion of Southern France. The change in code name from ANVIL to DRAGOON mischievously reflected Prime Minister Churchill’s view that he was pressed by the Americans into doing something that did not enjoy his full support.

The EUREKA Conference in Teheran (from November 28th to December 1, 1943) between Marshall Stalin, Prime Minister Churchill and President Roosevelt once again confirmed that there would be a landing in Southern France. The exact details of the plan were left in limbo due to the still present opposition by Churchill. However, Roosevelt did insist that both OVERLORD and ANVIL (now DRAGOON) would receive top priority in future plans.

The introduction of additional combat and support units to the troop list for OVERLORD as well as the current state of operations in Italy indicated that DRAGOON would have to be executed at dater later than that set for OPERATION OVERLORD. The difficult ANZIO OPERATION caused 68 LST’s to be diverted from resources previously OVERLORD. Thus the shortage of LSTs for the OVERLORD seaborne lift and necessity for maximum Troop Carrier resource for the airborne phase of OVERLORD dictated a change to the invasion sequence as originally developed at earlier strategic planning conferences.

General Eisenhower was a strong supporter of DRAGOON, even if the operation had to be pushed off to a later date. His primary concern was the achievement of a military victory in Europe in the shortest possible period of time. DRAGOON offered General Eisenhower the opening of the valuable Port of Marseilles, the second largest port in France, plus the chance to open up a second front in Europe, the practical outcome of which was to detain a large number of German forces in the Southern France theatre of operations and preventing them from reinforcing their forces in Normandy. Another important factor in Eisenhower’s arguing for DRAGOON was that it gave the Free French Forces a meaningful and important role in the liberation of their homeland.

It becomes apparent, then, the political versus military controversy surrounding what is perhaps one of the best planned and well executed invasion operations conducted during WWII. The success of the airborne phase of DRAGOON came about through the military professionalism and leadership displayed at all levels of staff and command from the highest headquarters and command level right down to the squad and initiative of the individual airborne trooper.

Despite a last minute plea from Prime Minister Churchill, on August 8, 1944, the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff cabled General Eisenhower that OPERATION DRAGOON would proceed as planned. This was the “green light and go” for the 1st Airborne Task Force (ABTF), a decision that played itself out over the Drop Zones and Landing Zones of Southern France.

Initial planning for the Airborne operation in DRAGOON was begun by the planning staff of the Seventh Army in February 1944. The status of airborne units in the Mediterranean Theater at that time materially influenced the planning at this stage as none of the Airborne or Troop Carrier Wings were fully prepared to undertake airborne operations.

The 51st Troop Carrier Wing, composed of three groups, had remained in the Theater after the inactivation of the XII Troop Carrier Command. However, only a portion of the 51st wing was available for airborne training because of the demand for Troop Carrier aircraft for special operations, air evacuation and general transport requirements. A few of these aircraft were intermittently attached to the Airborne Training Center located in Trapini, Sicily and later at the new location of the Airborne Training Center at Lido de Roma for a program of limited airborne training. At the Center, the First French Parachute Regiment, two Pathfinder Platoons and the American replacements received limited airborne training.

The British 2nd independent Parachute Brigade Group commanded by Brigadier C.H.V. Pritchard, Batteries A & B of the 463rd Parachute Artillery battalion commanded by Lt. Col. John Cooper and the 509th Parachute Infantry battalion commanded by Lt. Col. William P. Yarbrough were withdrawn from the front in Italy and given intensive training with a full Troop Carrier Group of the 51st Wing. The War Department was requested to provide an airborne division for employment in DRAGOON, but in lieu of this, a number of separate airborne units were shipped to the Theater. These were the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion commanded by Lt. Col. Wood G. Joerg, the 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team (PRCT) commanded by Colonel Rupert D. Graves and the 550th Glider Infantry Battalion commanded by Lt. Col. Edward I. Sachs. The 517th consisted of three parachute infantry battalions: the 1st Battalion commanded by Lt. Col. William J. Boyle, the 2nd Battalion commanded by Lt. Col. Richard J Seitz and the 3rd Battalion commanded by Lt. Col. Melvin Zais. The 460th Parachute Artillery Battalion of the 517th PRCT was commanded by Lt. Col. Raymond L. Cato and the remaining contingent of the 517th PRCT which was the 596th Parachute Combat Engineer Company which was commanded by Captain Robert W. Dalrymple. The 517th PRCT arrived from the States after just having completed its final large scale airborne training exercise and participation in the Tennessee Maneuvers. The 517th PRCT was attached to the fifth Army for tem days of battle experience in the lines and the 551st and 550th Battalions were attached to the Airborne Training Center, and then located in Sicily for training.

Thus, by the middle of June 1944, there were considerable airborne forces in the Theater which could be considered for airborne operations. In order to secure the utmost cohesion and to obtain the optimum results, it was decided to move the Airborne Training Center with its attached units, as well as the troop carrier aircraft (now increased to two full groups) of the 51st Troop Carrier Wing to the Rome area. Here was established a compact forward base for all airborne forces in the Theater.

Toward the first of July, 1944, the plans for OPERATION DRAGOON were made firm, including the use of a provisional airborne division made up of available units in the Theater. Major General Robert T. Fredrick, formerly commander of the First Special Service Force and later the commander of the 36th Infantry Division, assumed command of the composite force. Conferences were held immediately to secure the additional supporting units needed to organize such a balanced airborne force. Certain units on the DRAGOON troop list were earmarked for this purpose. Authority was requested from the War Department to activate those units which were not authorized on the Theater Troop List. By July 7th initial instructions relative to the organization of the Provisional Airborne Division known officially as the Seventh Army Airborne Division (Provisional) was disbanded and the 1st ABTF was constituted by a secret Adjutant General order of July 18, 1944. Assignment was to the North Africa Theater of operations and activation was accomplished by the reassignment of personnel from the Seventh Army Airborne Division (Provisional). This action was concurrent.

The following units which just a short time before had been assigned to the Provisional Airborne division, were then assigned to the 1st ABTF:

1 2nd British Independent Parachute Brigade Group

2 517th Parachute Infantry Regiment

3 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion

4 550th Airborne Infantry Battalion

5 1st Battalion, 551st Parachute Infantry Regiment (Reinforced)

6 460th Parachute field Artillery Battalion

7 463rd Parachute Artillery Battalion

8 602nd Pack field Artillery Battalion

9 596th Parachute Combat Engineer Company

10 887th Airborne Aviation Engineer Company

11 512th Airborne Signal Company

12 Anti Tank Company 442nd Infantry Regiment

13 Company A, 2nd Chemical Battalion (Motorized)

14 Company D, 83rd Chemical Battalion (Motorized)

15 172nd DID British Heavy Aerial Resupply Company

16 334th Quartermaster Depot Company, Aerial Resupply

17 Detachment, 3rd Ordnance Company (MM)

18 676th Medical Collecting Company (Designated 07/29/44)

19 5 Unit Pathfinder Platoons (These were unauthorized but were formed from 1st ABTF resources)

The 1st ABTF was then given a 5 per cent over strength by the assignment of parachute filler replacements from the Airborne Training Center. Meanwhile, the activation of the Task Force headquarters and headquarters Company, two additional batteries of the 463rd Parachute Artillery Battalion, the 512th Airborne Signal Company, and an anti tank unit to be designated the 552nd Anti Tank Company for operations because of the short time remaining before D-Day. The 442nd Anti Tank company was well trained prior to arrival in the Theater and when it was necessary to re-equip them with the British six-pounder, since the 442nd’s 57mm anti tank gun would not fit into the CG-4A glider, this well trained unit was able to make the transition in record time.

Due to the shortage of qualified airborne officers in the Theater, it was necessary to ask the War Department to make available a divisional staff for General Fredrick. Thirty-six qualified staff officers arrived in the Theater by air toward the middle of July. Most of these came from the 13th Airborne division and a few from the Airborne Center at Camp Mackall, north Carolina.

Certain other organizations were made available to the 1st ABTF on the basis of their being employed in the preparatory stages but not in the operation itself. These units included detachments from a Signal Company, a Quartermaster Truck Company, and some 400 replacements from the Airborne Training Center.

As of the middle of July, 1944, there were available in the Theater for airborne operations, two groups of the 51st Troop Carrier Wing. The third group was occupied with special operations. To provide sufficient lift for DRAGOON, additional troop carrier groups were called for by Allied Force headquarters. The total minimum of aircraft required for the operation was 450. On July 10, 1944, orders were issued placing the 50th and 53rd Troop Carrier Wings of the IV Troop Carrier Command 9then located in the United Kingdom) on temporary duty with the Theater. Each Wing contained four Groups of three squadrons each, reinforced by self-sustaining administrative and maintenance echelons and by the IX Troop Carrier Command Pathfinder unit, for a total of 413 aircraft. In addition to the personnel and equipment moved in organic aircraft, the Air Transport Command augmented the movement by transporting the 819th Medical Air Evacuation Squadron, various signal detachments, assorted parapack equipment and 375 organic glider pilots. The move, made in eight echelons via Gibraltar and Marrakech, required only two days. Two aircraft were lost reroute. Brigadier General Paul L. Williams, in command of two wings form the United Kingdom, arrived on July 16, 1944 and activated the Provisional Troop Carrier Division. By July 20th, the entire Provisional Troop Carrier Division had arrived in the Theater and was stationed at its designated airfields, prepared to carry out the mission.

Because there were approximately 130 operational CG4A and 50 Horsa gliders on hand, hurried steps were taken to secure the additional number of gliders required for the operation. Fortunately, a previous requisition for 350 CG-4A gliders from the United States had been made. It was necessary only to expedite this requisition in order to provide the glider lift. The British airborne forces had a sufficient number of Horsa gliders on hand in Theater to provide for the needs of the 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade Group. The shipment from the United States arrived as scheduled and the gliders were assembled in record time. They were ready for operational use ten days before D-Day. Unfortunately, because of the limited time constraints and the fact that only forty per cent of the new reinforced Griswold glider nose modification kits were available, it was decided not to attempt any modification prior to D-Day.

After considerable discussions, requests were made to the United Kingdom for approximately 350 additional glider pilots. Previous arrangements made to secure these pilots on three days’ notice were carried out and all the glider pilots arrived as requested.

Hurried preparations were required to assemble the necessary cargo parachutes and aerial delivery equipment needed to organize and prepare for the contemplated aerial resupply effort. As late as the 10th of July, the acting staff for General Fredrick submitted an overall requisition for this equipment to higher headquarters. By air and special water transportation, some 600,000 pounds of these supplies arrived in the Theater in time for the Operation. The last freight shipment was delivered to the 334th Quartermaster Depot on D-4. Every item that was requested arrived in time and the preparations for the operations ere carried out as scheduled.

As previously described, the Airborne Training Center and the 51st Troop Carrier Wing had been ordered to the Rome Area and established a compact airborne base at Ciampino and Lido de Roma Airfields. By the 3rd of July, and advance echelon of the Airborne Training Center was established at the Ciampino Airfield and was ready to operate. By the 10th of July, the Center with its attached units, the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion, and the 550th Glider Infantry Battalion were completely located at the Airborne Base. The Divisional Staff ordered from the United States for the 1st Airborne Task Force Headquarters could not arrive until approximately the 15th of July. Therefore, all other American units in the Theater were attached to the Airborne Training Center so that its staff could be used to assist I the expediting of the concentration of airborne troops. The 517th PRCT was ordered out of the line from Fifth Army control and arrived in the Rome Area by July 5th, 1944. The 509th PIB, already located at Lido de Roma was similarly attached to the Airborne Training Center for instruction. The various supporting arms and services which had been placed at the disposal of the Seventh Army Airborne Division (Provisional) were similarly attached. By July 17, 1944, General Fredrick had moved his Headquarters to Lido de Roma and was ready to proceed with the final organization and training of the airborne forces and the detailed planning of OPERATION DRAGOON. On the 21st of July, General Fredrick requested that the name of the Provisional organization be changed to the ‘1st ABTF, since the use of the term “Division” was considered a misnomer.

Although continuous planning for DRAGOON had been under consideration since February 1944, no final detailed planning was possible until the 1st Airborne Task Force and the Provisional Troop Carrier Air Division were organized and prepared to function. As of consequence of this, the final planning could not commence until almost the 20th of July. Upon his arrival, General Williams, the Commanding General , Provisional Troop Carrier Air division, approved the suggested plan of utilizing the previously selected Rome area as a training site. He also concurred in the choice of the previously selected take-off airfields located at Ciampino, Galera, Marcigliano, Fabrisi, Viterbo, Tarquinia, Voltone, Montalto, Canino, Orbetello, Ombrone, Grossetto, Fallonica, and Piombino. Subsequently, the Provisional Troop Carrier Air Division undertook primarily the planning aspects of the operation involving high level coordination, timing, routes, corridors, rendezvous, and traffic patterns. In general, planning for the details of the selection of Drop Zones (DZs), Landing Zones, (LZs) and composition of lifts were left to the Airborne and Troop Carrier units involved.

It was first decided that a pre-dusk airborne assault on D-Day should not be made, as this might jeopardize the success of the entire operation. Second, it was decided that it would not be necessary or advisable to launch the initial vertical attack after the amphibious assault had begun. The latter decision was reached in view of the wide experience of our Troop Carrier crews in night take-off operations, and because of the marked improvement that had been made in the pathfinder techniques. Consequently, the basic plan called for a pre-dawn assault. One proposed plan contemplating an immediate staging in Corsica was rejected because of lack of available Corsican airfields, and also because those fields available were located on the eastern side of the island, and their use would have necessitated a flight over 9000 foot mountain peaks. Such a flight would be difficult even for unencumbered transport aircraft, and for C-47’s towing gliders it was considered excessively dangerous. A further consideration was the fact that such an intermediate staging would have required the establishment of the airborne corridor south of the main naval channel, and would have necessitated the adoption of a dog-leg course for the flight.

After several conferences had been held at Seventh Army Headquarters, with all Army, Navy, Air and Airborne commanders concerned, the rough plan was drawn up and approved about July 25th, 1944. This plan envisaged the use of an airborne division prior to H-Hour with the dropping of the airborne pathfinder crews beginning at 0323 hours on D-Day. The main parachute lift of 396 plane loads was to follow, starting at 0412 hours and ending at 0509 hours. The first glider landing was to take place at 0814 hours and continue on through until 0822 hours. Later in the same day a total of 42 paratroop plane loads were to be dropped, followed by 335 CG-4A gliders starting at 1810 hours and ending at 1859 hours. The automatic air resupply which was to have part of the D-Day late afternoon mission was postponed at a late stage of the planning processes because of insufficient Troop Carrier aircraft and because Troop Carrier Command would not drop supplies from aircraft towing glider in the afternoon glider lift. The final plan provided for 112 plane loads to be brought in automatically on D+1. The remaining supplies were to be packed and held available for emergency use by either the 1st ABTF or by any Seventh Army unit which might become isolated.

The Troop Carrier routes selected were carefully chosen after due consideration of the following: the shortest distance, prominent terrain features, traffic control for the ten Troop Carrier Groups, naval convoy routes, position of assault beaches, primary aerial targets, enemy radar avoidance, excessive dog legs, prominent landfalls, and position charts of enemy flak installations. This route logically followed the Italian coast generally from the Rome area to the island of Elba, which was used as the first over water check point, followed by the tip of the island of

Corsica and proceeded on an azimuth course over Naval check points to the landfall just north of Frejus and Agay. Complete plans were made with the navy on the position of this airborne corridor, and detailed information concerning it was widely disseminated among the naval forces.

Because of high terrain features in the target area it was decided that it would be necessary to drop the paratroopers and release gliders at exceptionally high altitudes varying from 1500 to 2000 feet. Glider speeds for towing were set at 120 M.P.H. and dropping speed 110 M.P.H. the formation adopted for the parachute columns was the universal “V of Vs” in nine ships in serials of an average of 45 aircraft, with five minute intervals head to head between serials. The glider columns adopted a “pair of pairs” formation echeloned to the right rear. Serials made up of 48 aircraft towing gliders in trail were used with eight minute intervals between serial lead aircraft. Parachute aircraft employed a maximum payload of 5430 lbs., Horsa gliders 6900 lbs., and the CG-4A gliders a total of 3750 lbs.

Difficulty in the procurement of maps and models proved to be a serious inconvenience in the planning and preparations for the operation. Map shipments in many instances were late in arriving or were improperly made up. Terrain models on a scale of 1:100,000 were available but the most useful terrain model, a photo-model in scale of the 1:25,000 was available only in one copy, which was wholly inadequate to serve both the Provisional Troop Carrier Division and the 1st Airborne Task Force. The blown-up large scale photographs of the DZ-LZ areas in particular were excellent, but these arrived too late for general use. The original coastal obliques were not of much assistance to the Provisional Troop Carrier Air Division since the run-in form the IP (First landfall) was not adequately covered. These late photographic studies uncovered the previously unknown element of anti-glider poles installed on the LZs. All earlier photo studies had failed to reveal this pertinent information. An excellent terrain model was turned out by the 2nd British Independent Parachute Brigade and it was of great assistance to that unit for the operation.

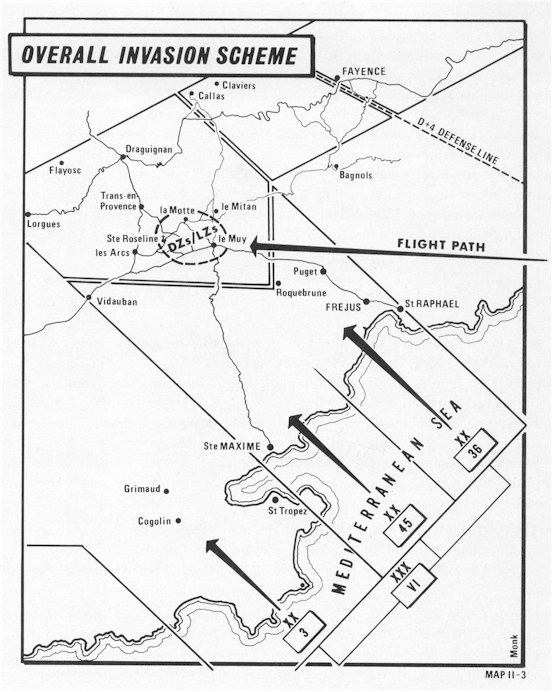

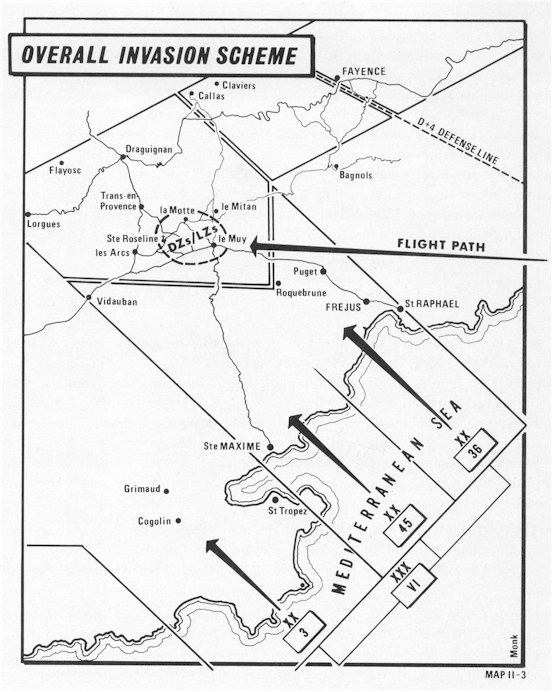

Figure 1: Overview of Overall Invasion Plan

By the middle of July nearly all the airborne units to be employed on OPERATION DRAGOON had been assembled in the Rome area. An intensive final training program had begun by the 1st ABTF in conjunction with the Airborne Training Center. Of the Airborne units to be used in the OPERATION, only the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion and the 2nd British Independent Parachute Brigade Group had received any recent combined airborne training with the Troop Carrier units. The 517th PRCT had just come out of the line with the Fifth Army as had the 463rd parachute Artillery Battalion. Other units, such as the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion and the 550th glider Infantry Battalion had but recently arrived overseas and had been given a course in ground and airborne refresher training at the Airborne Training Center.

A particularly urgent task was the training of the newly chosen glider borne troops. A combined glider school was set up and instruction commenced in the mechanics of loading and lashing for the units involved. The units involved in this difficult last minute procedure were the 602nd Pack Field Artillery Battalion, the 442nd Infantry Anti Tank company, the 887th Airborne Aviation Engineer Company, Company A, 2nd Chemical Battalion, Company D, 83rd Chemical Battalion, and the various other units such as the Division Ordnance Detachment and the Medical Collecting Company. Once these troops had finished the course in loading and lashing, they were given orientation flights and finally one reduced size practice operational landing on a simulated LZ.

The Provisional Troop Carrier Air Division Pathfinder unit went to work with the three airborne pathfinder platoons and thoroughly tested the radar and radio aids to be used in the operation. This training was divided into three phases, the first being concerned with the technical training with “Eureka” sets, M/F beacons, lights and panels. Tests were made to locate any deficiencies in either the training or the equipment to be used. The second phase was devoted to practice by the crews in using the equipment as a team. All the teams practiced in setting up and operating the equipment under all possible conditions. The third phase emphasized actual drops with full equipment in which every attempt was made to secure the utmost realism in the preparatory exercises. Small groups of parachute troops were dropped on the prepared DZs to test the accuracy of the pathfinder aids.

Due to the lack of time and the difficulty of re-packing the parachutes in time for the operation, it was impossible for the 1st airborne Task force to stage any large scale realistic final exercise. The various individual units did participate in practice drops to the fullest possible extent, generally using a skeleton drop of two or three men to represent a full “stick” of paratroopers, the reminder of the unit already being on the DZ so that the assembly procedures could be tested and experienced. A combined training exercise with the Navy, however, was scheduled. All naval craft carrying water-borne navigational aids were placed in the same relative positions as in the actual operation. A token force of three aircraft per serial were flown by all Serial Leaders over these aids, the flights flown on the exact timing schedules, routes and altitudes as were used in the operation. Two serials of 36 aircraft each were flown over this same route in the daylight in order that the Naval Forces would become acquainted with the troop Carrier formations. Further practice runs were made by the Troop Carrier units in conjunction with the 31st and 325 fighter Groups so as to work out the details of the fighter Cover Plan and the Air/Sea Rescue Plan.

In view of the fact that the Task Force was composed of units that had not previously worked together, training of combat teams, as organized for the operation, was emphasized to further successful operations after landing. Training of each newly organized combat team was conducted on terrain carefully selected to duplicate, as nearly as possible, the combat teams sector within the target area.

The problem of securing and organizing qualified personnel and then training those units that had to be activated on short notice proved to be difficult. Such highly specialized personnel as are required for an Airborne Signal Company or for an Airborne Divisional Headquarters were extremely difficult to find in an overseas theater. Consequently, these personnel had to be located in the local Replacement Depots or at the Airborne Training Center and then trained for the specific positions they were to fill. The highest praise is due General Fredrick and his staff, and the Airborne Training Center for the manner in which this task was accomplished.

It was fortunate that the larger elements of the Task Force, particularly the Combat Teams, were already well trained. Some of them were battle-seasoned and nearly all were accustomed to providing for themselves since each was basically designed to be a separate regiment, battalion or company. This unique circumstance allowed the units not only to look after their own requirements, but also permitted them to aid the 1st ABTF as a whole during this period of training.

The Operation - Airborne Phase

The night of D-1 was clear and cool in the take-off areas used by the Airborne Forces in DRAGOON. The Troop Carrier units were at their stations in the ten airfields extending from Ciampino near Rome to Fallonica, north to Grosseto. Due to the serious lack of ground transportation, it was necessary for the bulk of the Task Force, except for the British 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade Group, to commence the movement to the dispersal airfields by D-5. By D-2, the Airborne Forces had been shuttled from their training and concentration areas near Rome to their designated airfields. The C-47 aircraft had all been deadlined, checked thoroughly and were in excellent condition for the invasion flight. All of the preliminary checks had been completed at the glider marshalling airfields and they were ready to roll. A feeling of assurance as to the outcome of the operation prevailed among all elements.

As to be expected in any airborne operation, prevailing weather was to be important and could influence the parachute drops. Once the target date had been set it could not be changed for the benefit of the Airborne Forces, even though it necessitated a drop with out the assistance of moonlight. It had been hoped that the drop could be made on a clear night so that the Troop Carrier aircraft could identify large hill masses and coastal features as possible check-points. However, on August 14-15, 1944, all of Western Europe was covered by a large flat high pressure area centered over the North Sea. A portion of this “High” had broken off and had settled over the main target area. This did preclude the probability of any sizeable storm or heavy winds, and the only threat was one of accumulating fog or stratus. Consequently, the forecast for the operation was clear weather to Elba, followed by decreasing visibility until the DZs were reached, at which time the visibility was expected to be from 2 to 3 miles. Actually, the haze was heavier than anticipated and the visibility was less than half a mile on the DZs. The valley fog that had completely blanketed the early parachute operation had dispersed by 0800 hours. Fortunately, this was in time for the morning glider mission. Considerable navigational difficulties arose from the fact that the wind forecast was almost 90 degrees off the direction initially indicated. Consequently, the navigators could make necessary corrections only by use of check-points over the water route. Fortunately, the wind did not reach high velocity and was less than six M.P.H. on the DZs.

The operation was prefaced by a successful airborne diversion designed to serve two purposes in the Cover Plan. First, it was to create the illusion of a southern airborne corridor; second, it was to simulate a false airborne DZ by dropping rubber parachute dummies into selected areas. The six aircraft used on this mission dropped “window” enroute to give the effect of a mass flight and at 0205 hours on D-Day they dropped 600 parachute dummies as panned on false DZs located north and west of Toulon. German radio reports indicated the complete success of this rouse. The rifle simulators and other battle noise effects used in the diversion functioned well and added to the realism of this feint.

The Airborne operation began shortly after midnight on August 14-15, 1944. Aircraft were loaded, engines were warmed up and the marshalling of aircraft for takeoff was underway at 0300 hours. At the same hour as the first Troop Carrier aircraft took off with their load of three Pathfinder units. During the aircraft marshalling phase several aircraft received minor damage and one was demolished. One aircraft from the 439th troop Carrier Group crashed and burned on take-off, two aircraft struck trucks and received minor damage and two other aircraft from the same Group had a collision while rolling out on the taxi ramp. One other aircraft suffered damage to a wing when one of its wheels hit a poorly filled hole on the airfield, and another suffered damage due to the premature release of a parapack. Considering that the take-off was from prepared landing strips without any moon to aid the poor visibility caused by excessive dust, the success of this phase of the operation is unquestioned. An estimated eight glider had difficulty on take-off and had to be unloaded so that the substitute gliders could be employed to lift the loads.

The Pathfinder Mission is of interest in that instead of the reported “complete success” of the mission, later facts revealed that it was less than fifty per cent effective. Nine Pathfinder aircraft divided into three serials were each employed in such a manner that three teams would be dropped on each DZ. The Lead Serial, supposed to drop Pathfinders from the 509th and 551st Parachute Infantry Battalions plus that of the 550th glider Infantry Battalion at 0323 hours lost its way and circled back to sea to make a second run a the correct DZs. After circling for about half an hour one aircraft dropped its Pathfinder Team and went home. The other two aircraft separated after that and one dropped its team about 0400 hours. The last Team jumped at 0415 hours on the sixth run in on the target. Lost in the woods and far from their objective, none of the three Teams were able to reach the Le Muy area in time to act as Pathfinders. The Second Serial was to drop its Pathfinders from the 517th PRCT at 0330 hours. The actual drop was at 0328 hours. The 517th Pathfinders landed in the woods three and a half miles east of DZ “A” and just east of Le Muy itself. A two minute jump delay would have put them right on target. To make matters worse they were attacked and spent time beating off the assault. They arrived at DZ “A” at approximately 1630 hours and set up a Eureka Beacon, a MF Beacon, and a “T” Panel which was of assistance to the afternoon missions for this area. The Third Serial carrying the Pathfinders form the British 2nd Independent Brigade Group, dropped on DZ “O” at 0334 hours, exactly on schedule. By 0430 hours they had two Eureka Beacons in operationabout 300 yards apart along the axis of the approach. They also set up two lights for assembly purposes. This Pathfinder drop was the most accurate of the three.

Approximately one hour after the Pathfinder aircraft took off the main parachute lift, composed of 396 aircraft in nine serials, each averaging 45 aircraft, took off and proceeded on their assigned courses. The flight toward the designated DZs was marked by no untoward incident. Amber downward recognition lights were employed until the final water checkpoint had been crossed. Wing formation lights were similarly employed and no instance of friendly naval fire on the Troop Carrier aircraft was reported. No enemy aircraft was encountered during the flight. Of particular note is the fact that over four hundred Troop Carrier aircraft had flown in relatively tight formation under operational strain for some five hundred miles without incident. The many hours of time devoted to training in night formation flying had produced excellent results.

The radio, radar and other marker installations undoubtedly helped to save the day in terms of the success of the mission. The Eurekas which had been installed at each Troop Carrier Wing Departure Point, the Command Departure Point, the North East tip of Elba, Giroglia Island (North Corsica), on the three marker Beacon boats spaced 30 miles apart on curse from Corsica to Agay, France (the first landfall checkpoint), all worked exceedingly well with an average reception range of 25 miles. Holophane lights similarly had been placed at these positions and did aid the navigators in their work with the contrary wind currents. Their reception was an average of 8 miles until the DZs were reached, at which time they became invisible because of the haze and ground fog. MF Beacons (Radio Compass Homing Device) were installed at Elba, North Corsica and on the central oat marker beacon and dropped on the DZs along with the Eurekas and the Holophane lights. Many pilots reported that they picked up these signals up to 50 miles away and often kept the aircraft on beam when they occasionally lost the Rebecca signal on their Eureka, which in to many cases exhibited a tendency to drift off the frequency despite constant operational checking. It should e emphasized again that the entire parachute drop was made “blind” by the Troop Carrier aircraft who had to depend on these MF Beacons and Eureka sets for their signal to drop the paratroopers. Brigadier C.H.V. Pritchard, Commanding Officer, 2nd British Independent Parachute Brigade Group felt that this single deficiency could have jeopardized the complete operation.

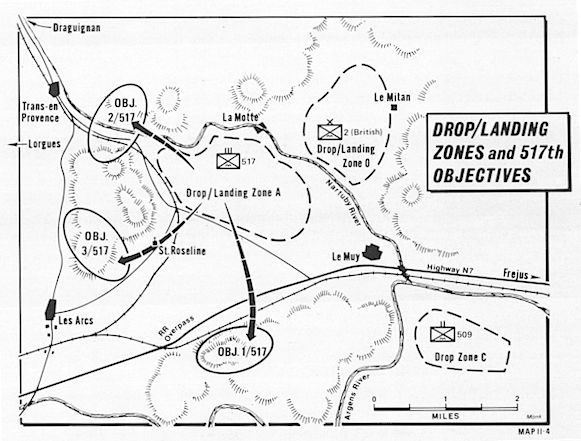

Figure 2: Initial 517th PRCT D-Day Drop/Landing Zones and Objectives

Initial reports stated that the parachute drop was eminently successful and it was given a score card rating of 85 per cent accuracy. This was later down graded as the incoming reports became more accurate and detailed in content. Despite the accuracy of the reporting system sufficient paratroopers landed on the DZs or in the immediate vicinity thereof, in areas which for all practical purposes can be considered as contiguous to the DZs and from which terrain the parachute forces were in positions which allowed them to carry out their assigned missions. This was accomplished despite the handicaps of no moon, general haze, and heavy ground fog. An estimated 45 aircraft completely missed their designated DZs. Some of these dropped their paratroopers as far as 20 miles from the selected areas.

Among the aircraft that missed the DZs were twenty in serial Number 8, which released their troops prematurely on the red light signal. The only plausible explanation that can be offered is that a faulty light mechanism in one of the leading aircraft must have gone on green prematurely and the troops in the lead aircraft jumped according to this signal. The paratroopers in the following aircraft, on seeing the leading aircraft’s troopers jump, probably did likewise and jumped even though the red signal still showed in their won aircraft. This group was principally comprised of elements of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion and about half of the 463rd Parachute field Artillery Battalion. Two “sticks” of paratroopers landed in the sea off of St. Tropez, near Cannes. The remainder made ground landings in the vicinity of these two towns. Although far from the designated DZ, these elements organized themselves, made contact with the French Resistance Forces, and proceeded to seize and hold St. Tropez. Approximately 25 aircraft from another Troop Carrier Group mistakenly dropped their paratroopers some 15 miles north of Le Muy near Fayance. The troops in this instance comprised part of the 5th Scots Parachute Battalion of the British 2nd Independent Parachute Regimental Brigade Group, and elements of the 3rd Battalion, 517th PRCT. Although some 20 miles from their DZ, these troops either undertook individual missions or fought their way back to their own units in the proper Objective Area. By evening of D-Day, most of this group was reassembled on DZs “A” and “O”. The Task Force Chief of Staff, along with the Task Force Surgeon and other key staff officers were among this group. DZ “A” generally west of Le Muy had a tendency, during the drop, to become merged with DZ “O”, slightly northwest of this key town on the Vargennes Valley, which caused considerable confusion later on in the day. This inadvertent merging of the two DZs also produced some confusion and difficulty during the period of the equipment bundle recovery. This confusion was further increased because the British 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade Group was using different equipment from that of the 517th PRCT on DZ “A”.

The terrain of the DZs on which the paratroopers landed was in general excellent for such an operation. DZs “A” and “O” covered an area of small cultivated farms consisting mainly of vineyards and orchards. There were very few large buildings, telephone wires, tall trees and other formidable obstacles. The anti-airborne poles established in the Parachute Drop Areas were not sharp or placed in sufficient density to obstruct the parachute landings to any material degree. A total of 175 paratroopers, scarcely more than 2 per cent, suffered jump casualties. DZ “C” on which the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion Combat Team jumped was a hill mass more rugged than the ground of the other DZs, but even this rougher terrain did not interfere with the success of the jump.

Serial Number 14 (the first of the glider serials) made up of supporting artillery and anti tank weapons for the British 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade Group departed as scheduled for its 0800 hours glider landing, but was recalled because of heavy overcast. The flight circled for one hour and landed at 0900 hours. One glider and tug aircraft had to turn back. One glider ditched off shore and another disintegrated in mid-air over the water (the cause was subsequently laid to structural failure0. The stakes driven into the ground all over the LZs did not prove to be difficult obstacles, even though the poles did cause considerable damage to the gliders and in some instances to their loads. The anti-glider poles served in many instances as additional braking power for the gliders, since the poles were small, planted at shallow depth, and were too widely dispersed to perform their intended mission. Evidently, the French farmers who were forced to plant the anti-airborne (glider) stakes had done the minimum work they could in this forced construction. These poles were on the average of 12 feet high and 6 inches in diameter. They had been driven in the ground less than two feet and were generally more than 30 to 40 feet apart. Serial Number 16 was a parachute load made up of the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion. It dropped accurately on DZ “A” at 1800 hours as planned. This drop was followed up rapidly by continuous glider serials Numbered 17 through 23, nine gliders was reported to have been released prematurely, four of which made water landings. A large percentage of their crews and personnel were saved by prompt action on the part of the Navy. The landing skill of our glider pilots was outstanding. Although the 1000 foot interval adopted for towing caused considerable jamming over the LZs, these pilots affected excellent landings. Several pilots ground-looped their gliders to avoid obstacles and still brought in personnel and cargoes safely. Another reason for the crowded conditions over the Landing Zones was a notable tendency on the part of successive flights to seek additional altitude as a result of the ‘accordion movement” of the flights enroute. In turn, this progressively created a greater mass of aircraft and gliders being over the LZs at any one time than had been contemplated. Further difficulty arose because the pilots of the early glider lifts landed on the best and most obvious sections of the Landing Zones instead of in their own designated sectors. On their arrival, the later lifts consequently found that their assigned landing areas were almost entirely occupied with gliders which forced them to seek alternate and less desirable areas. This was further compounded by the situation wherein two glider serials were released so close together that they both were in the air at the same time over the same already crowded LZ. Quick reaction was the order of the day for one did not get a second chance to make a landing run in a glider. The pilots simply had to dig in on their landings because of the limited space. These abrupt, heavy landings, did cause excessive damage to the gliders, primarily because of the lack of the ‘Griswold Nose” modification. The glider pilots demonstrated great presence of mind, prompt action and skillful maneuver saving many lives and much valuable airborne equipment. It was established by D+6 that not more than 125 glider-borne personnel were injured in these landings. Although not encountered in the immediate objective area, as a matter of interest, it is worthy to note that in the Frejus area outside of the Drop Zones, there was a second type of anti-glider obstacle which consisted of small but sturdy sharpened stakes some 18 inches high, firmly imbedded in the ground and connected by wire which could play havoc on the belly of any glider landing on terrain prepared with such an obstacle.

In general, the problem of air re-supply did not become as urgent as had been expected. Absence of serious enemy opposition caused ammunition expenditure to fall below the anticipated amount. The initial plan for bringing in the first supplies by air on D-Day was consequently changed so that it was not until 1100 hours on D+1 that two Troop Carrier Groups brought 116 aircraft loaded with supplies. The aircraft arrived over the DZs on schedule but at an altitude well over 2000 feet, which made accurate dropping extremely difficult. A rather stiff breeze, coupled with the high altitude and the merging of the DZs (“A” and “O”), caused much of the dropped equipment and supplies to get into the hands of the wrong units on the ground. Well over 95 percent of the 1700-odd bundles dropped by parachute landed safely, but much of the specialized equipment failed to reach the units which had requested it. Subsequently, re-supply missions carrying emergency signal and medical supplies were flown again on the night of D+1. Although these drops had to be made at night by pathfinder aids the success of these missions was above average, except that again the high altitude caused excessive scattering of equipment. The 334th quartermaster Depot Company, Aerial Re-supply, aided by the Parachute Maintenance Section of the 517th PRCT, packed over 14,000 parachutes and 1000 tons of equipment for the operation and deserved commendation for the outstanding work they accomplished. The British Allied Air Supply Base deserves the very same credit and a well done for their contribution.

While in the grand scheme of the whole operation, enemy strength and actions could be considered light, it was a far different matter from the troopers standpoint as he and his comrades, in individual actions and small unit combat situations, struggled to get back to their designated DZs and Assembly Areas, from which they had been separated, due to a 50 percent dropping error during the final run into the Objective Area. To these “mission oriented” troopers this was in every sense of the word a “big war”. How the Airborne Forces accomplished their missions under adverse conditions can best be illustrated by taking the largest airborne unit involved during this phase of the operation, the 517th PRCT, and highlight its D to D+1 combat actions.

The 3rd Battalion of the 517th PRCT dropped approximately 15 to 20 miles northeast of DZ “A” and was scattered over 8 miles of rough terrain from Élans east through Fayence to Tourettes and Callian, all a good days march from DZ “A”. As this unit began to assemble and look for its equipment, three major sub-sections of this unit emerged; the first sub-section consisted of the first 10 aircraft loads dropped near Seillans which included most of Company I, the Battalion Commander, plus a Battalion headquarters contingent all totaling 160 troopers; the second contingent consisted of 60 troopers from the Battalion Headquarters Company and G and H Companies who dropped in the vicinity of Tourettes; and finally, the third group of over 200 troopers from units within the Battalion plus members from the 596th Parachute Combat Engineer Company and members of Regimental Headquarters and Service Companies who had all been attached to the 3rd Battalion for the drop. This entire last group had been dropped in the vicinity of Callian. The combined strength of these sub-sections totaled about 480 troopers. About 35 troopers were injured during the drop and had to be left behind, with an escort, due to the nature of their injuries. Seventy-five troopers caught up later and about 50 others were too far away to join up and so they resorted to independent actions of opportunity. By 0800 hours the Battalion Commander, Lt. Col. Melvin Zais, with almost all of his Battalion now intact commenced to march to be back to his Objective Area which was some distance away.

The 1st Battalion, 517th PRCT was also dropped in a scattered pattern over an area 30 to 40 square miles west to northwest, and southwest of trans-en-Provence. At daylight Captain Charles La Chaussee of Company C and Lt. Erle Ehly of Battalion Headquarters Company, had managed to get together about 150 troopers in the Battalion Assembly Area and had made the decision to move out to the Battalion Objective Area without further delay. At this point, the Battalion Executive Officer, Major Herbert Bowlby, joined them and took command. The Battalion Commander, Major William Boyle, landed about 4 to 5 miles from Trans and having lost about two-thirds of his “stick” in the dark gathered the remaining 5 troopers and took off for his Objective Area. He entered the outskirts of Les Arcs in the afternoon and found and additional 20 troopers that included the Battalion S-3 and the Assistant Battalion Surgeon. Gathering up this group, Major Boyle again started out for the Objective Area. On the way he and his party got into a firefight with about 300 of the enemy and the situation became “touch and go”.. Additional 1st Battalion troopers coming in from the northwest joined Major Boyle until his force numbered 50 or more troopers. He was forced to set up a perimeter type defense on the southeast edge of Les Arcs and dig in. A third group from the same Battalion managed to meet up with Captain Donald Fraser whose Company A had been designated as the 517th PRCT Reserve Force. Captain Fraser managed to get together about 200 troopers to take over the Area of operations that was previously assigned to the 3rd Battalion, 517th PRCT on the west of the Chateau Saint Rosaline; and Major Boyle encircled in the vicinity of Les Arcs.

The 2nd Battalion, 517th PRCT, commanded by Lt. Col. Richard Seitz, at about 50 percent strength, was on its way to its Objective Area by daylight after having landed about a mile from its Drop Zone, which was DZ “A”. By noon of D-Day the 2nd Battalion minus Company F was on its Objective. Company F which had dropped with part of the Regimental headquarters and part of the 596th Parachute Combat Engineer Company in the vicinity of Le Muy rejoined the 2nd Battalion, 517th PRCT on the Battalion Objective later in the afternoon.

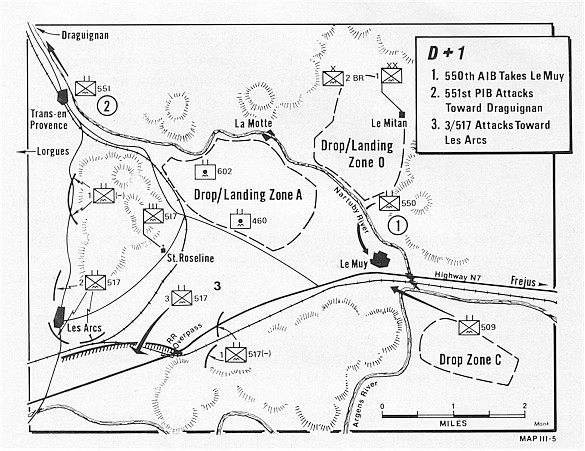

The versatility of the airborne troops was demonstrated even more when the 2nd Battalion, 157th PRCT was ordered on D+1 to relieve the Regimental Reserve commanded by Captain Fraser and also to extricate the 1st Battalion Commander and his group in the vicinity of Les Arcs.

Meantime, the 3rd Battalion, 517th PRCT arrived at the 517th PRCT Command Post at Chateau Saint Roseline about 1600 hours on D+1. Despite exhaustion from the forced march the Regimental Commander, Colonel Rupert Graves, ordered his 3rd Battalion to take Les Arcs by nightfall. This action was essential as General Lucien Truscott, Commanding General VI Army Corps, wanted Les Arcs cleared of enemy by the following day. At daylight, the 3rd Battalion was 800 yards short of Les Arcs. The advance was resumed and Les Arcs was taken.

The town of Le Muy, which had been assigned to the British 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade Group as a D-Day Objective, proved rather difficult to take even though the British troopers had captured the main bridge leading into town well ahead of schedule. General Fredrick, Commanding General of the 1st Airborne Task Force, reassigned this mission to the newly arrived 550th glider Infantry Battalion which captured Le Muy on D+1.

The 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion with the 602nd Pack Artillery Battalion (Glider) attached, was ordered by the 1st ABTF at 1100 hours on D+1 to attack Draguigan and seize the town. Throughout that afternoon and into the night the 551st fought its way into this town. The Commanding General of the German Army LXII Corps, General Neuling and his staff, along with several hundred troops that included a special officer cadet class, surrendered. This was done in sufficient time to permit a special mobile force from the U.S. Army VI Corps to pass through the town on D+3 on their way to the Rhone and beyond.

The 509th parachute Infantry battalion was of great assistance to the amphibious forces by making early contact with these forces and subsequently easing their movement inland. Also of note is the fact that the 11 out of 12 pack howitzers of the 463rd Parachute Artillery Battalion were operative in less than an hour after landing. Likewise, the 4.2 Mortar Companies and the 602nd Pack Artillery Battalion (glider) which came in by glider were ready for action shortly after landing. The rigorous parachute training for the artillery units paid off and was exemplified by the 460th Parachute Artillery Battalion in the way they man-handled their howitzers in order to keep up with the ever changing situation that characterized this operation. Although insufficient targets materialized to require much use of this fire-power, the artillery units never the less were prepared to furnish artillery support when and as needed. It was comforting for the infantry troopers to know that they were there and ready.

By D+3 the 1st ABTF had commenced to reorganize in the vicinity of Le Muy. Following the reorganization it proceeded to advance along the Riviera towards Cannes, Nice and the Italian Border. The British 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade Group was taken out of action and preparations were made to return it to its base in the Rome area for further operational use. The First special Service Force replaced the British Paratroopers, and the 1st ABTF then continued to advance along the coast, meeting determined enemy rear guard opposition. These operations of the 1st ABTF toward the Franco-Italian border were not restricted to the coast, but extended to a point some 65 miles inland. As has always been the case when airborne troops are retained in the line in an offensive capacity, they experienced back-breaking difficulty in transporting their heavy supporting arms and ammunition. The fluid, rapid advance of the Seventh Army as a whole made it difficult for the Seventh Army to provide the necessary vehicles for the 1st ABTF. As a result, the paratroopers in many cases hauled their 75mm pack howitzers for some 60 or 70 miles over the rugged Riviera coastline. Fortunately, a number of captured enemy vehicles, together with the units organic transport brought in by gliders, did make the movement feasible.

While the 517th PRCT was used to portray the versatility and aggressiveness of airborne units the very same qualities were found and able demonstrated time after time by the other 1st ABTF units in DRAGOON. The 1st ABTF, at the close of the airborne operations phase of DRAGOON had all the necessary credits to recommend its retention as a Separate Airborne Force, to be retained at the Theater level, for repetitive airborne operations.

For all practical purposes, the airborne phase of DRAGOON was over by D+2 due to the earlier than expected link-up with the Amphibious Forces late on D+1. Combat actions continued in the airborne objective area due to the scattered nature of the combat actions, but the enemy was in complete disarray and had difficulty in conducting any coordinated actions of significance. From this point on the 1st ABTF was to play the role of a light special type of divisional size force as it protected the Franco-Italian border from enemy inroads. It was at point in time that the lightness of airborne units that made them so well suited for airborne assaults now went against them due to their lack of ground mobility which was the key to staying power in extended ground combat operations. It was this overpowering lack of mobility that caused General Devers, Commanding General of Sixth Army Group, to relegate the 1st ABTF to a security type of role.

During OPERATION DRAGOON the Provisional Troop Carrier Air Division flew 987 sorties and carried 9,000 airborne troops, 221 jeeps and 213 artillery pieces. The sorties flown also included 407 towed gliders and carried over 2 million pounds of equipment into the battle area for the 1st ABTF. One aircraft was lost as a result of the OPERATION itself and the losses in aircraft from the period of movement from the United Kingdom to the conclusion of the OPERATION totaled only nine. No Troop Carrier personnel other than glider pilots were known to have been killed; 4 were listed as missing, and 16 were hospitalized. The balance of the 746 glider pilots dispatched on the operation had returned to their organizations.

On the airborne side of the picture, 873 American Airborne personnel were listed as killed, captured, or missing in action with 327 hospitalized on D+2. By August 20th, (D+5), this figure had fallen to 434 still listed as killed, captured or missing in action while many of the hospital cases had returned to their units for further action. The British 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade Group had 181 troopers listed as missing in action and 130 men hospitalized. Later reports indicated that 52 British paratroopers had been killed and that 500 replacements had been requested by the American units and 126 replacements from the British unit. By D+2 over 1000 prisoners had been taken by the American Forces and nearly 350 by the British Brigade. By D+8, this figure was well over 2000. The total jump and glider crash accidents amounted to 283 or approximately 3 per cent of the operational personnel involved.

The recovery of the parachutes both of the personnel and cargo types was very low. As of September 1st, not more than 1000 parachutes had been sent to the Rome base for salvage and repair. Similarly, the gliders that could be used again were very small in number. A survey of the LZs indicated that fewer than 50 of the gliders could be salvaged without excessive cost.

Conclusions, Summary and Final Conclusions

The following Conclusion, Summary and Final Conclusions are taken directly from a declassified Allied Forces Headquarters report on Airborne Operation Dragoon dated September 4, 1944, that was prepared by the G-3 Section Airborne Advisor, Major Patrick D. Mulcahy. As this analysis unfolds, one must remember the information contained in this report is a snapshot in time immediately after the operation and a retrospective analysis. It should be kept in mind that this analysis was conducted by the Allied Forces Headquarters Report written by a member of the “airborne fraternity” who like so many of the airborne troops found the new from of airborne warfare as daring and exciting and did not understand the meaning of the words “it can’t be done”. The introductory paragraph of the Allied Forces Headquarters Report (AFHQ), under the heading “conclusions” is typical of this attitude. What follows is the Conclusions, Summary and Final Conclusions of the AFHQ Report:

1. The most obvious criticism of the airborne plan for “DRAGOON” was that it was not bold enough. The execution of the missions assigned the force were handily executed with precision. Although it is the worst kind of Monday morning quarterbacking, it could be said that a plan for a drop as far back as Grenoble could have been used to far better advantage, such, in retrospect, would have been better. A second point along this same line is the fact that instead of being used in the pre-H hour assault, the airborne troops could have been held in readiness until the withdrawal conditions became obvious, at which time they could have been dropped by D+2 or D+3 further inland to prevent any further retreat en masse up the Rhone Valley. The French Parachute Regiment is and has been available, and could have been used in this mission along with elements of at least part of the Airborne Task Force.

2. The airborne plan was well planned and thought through, and within the framework of the plan could hardly have been better laid on by the detailed planners.

3. The use of Pathfinder Aircraft and airborne Pathfinder Teams, above everything else, was well planned and executed. Without the use of radar, radio and other aids, there simply could have been no airborne mission. The development of the PPI used in the Pathfinder aircraft has made possible airborne operations which could not have been considered a year ago.

4. The routes selected for the mission were excellent. Utilizing all possible check points, shortest distances, avoiding dog-legs or enemy flak positions while making landfall by the prominent, irregular coastline—all while managing to stay out of the Naval channel in the prescribed 10 mile corridor, made possible the excellent results obtained.

5. Despite every precaution certain Troop Carrier A/C did pass over individual naval vessels. The Navy by their disciplined action demonstrated that the bitter lessons learned at Sicily had produced results.

6. The 334th Quartermaster Depot Company which is the American Theater Re-supply organization turned in a magnificent job in their organizing the supply base at Galera, securing the supplies and packaging them in time for the operation. This unit packed over 10,000 parachutes in a seven day period and prepared for dropping five complete days of supply (sic) for the Airborne Task Force, a total of some 1000 tons.

7. The altitudes flown, speeds adopted, formation used both for the parachute dropping and air landing were excellent, with the exception that the “V of Vs” formation flown at an excessively high altitude for the supply dropping caused considerable drifting and scattering of supplies. Had these missions been flown by single aircraft in extended column at a lower altitude the necessary pin point dropping could have been effected (sic). This is particularly true because of the lack of enemy air and flak opposition.

8. Pre-operational training was excellent considering the short time available for such training. The airborne troops could have used one mass drop per unit on a final exercise but the time element precluded it. The combined Airborne-Naval exercise proved to be particularly instructive.

9. The choice and organization of the take-off airfields was good. Much credit must go to the 51st Troop Carrier Wing which made possible the rapid preparation and occupation of these airfields by much work prior to the se up; of the Provisional Troop Carrier air division (PTCAD).

10. Credit must also be extended to the Airborne Training Center without whose help the Provisional airborne Division could hardly have been effected. Despite the fact that the Center itself moved into the Rome Airfield Base Area but a few days before the Division (1st ABTF) they aided General Fredricks in countless ways to expedite his work.

11. the efforts made by the Airborne and Troop Carrier headquarters to have the Army, Nay and other air forces become familiar with their routes, procedures, formations and even individual troops were very successful. Squads of parachutists were taken in the various assault battalions of the 3rd, 36th and 45th Divisions in order to preclude any such mishaps as occurred on previous airborne operations when our troops fired on our paratroopers. The marking system employed by the Troop Carrier Command is also commended. The black and white stripes became well known to the Navy and other Air Force units prior to the operation and served to decrease any possibility of improper identification.

12. The glider assembly program was particularly well managed. By D-Day 407 well put together gliders were assembled and ready for operations, which was a brilliant feat since the vast majority of these gliders had but recently arrived form the United States by boat.

13. The weather forecasting while generally good, proved weak with respect to the direction of the prevailing winds during the flight. Had this wind been stronger or had the over water beacons failed, the navigators in all probability could have not made their off-sets which would have certainly jeopardized the complete mission.

14. The diversionary effort using the parachute dummies and “window’ proved quite effective. It is recommended that further use be made of this equipment in future operations.

15. While the photo coverage of the area was generally good, most of the photos which were effective arrived at such a late date that any changes in the plans could hardly be made for fear of compromising the entire mission. This was in particular demonstrated by the late discovery of the anti-airborne poles on the DZs. Likewise more terrain models of a scale of 1:10000 or 1:25000 must be made available both to the airborne and troop carrier units for airborne operations. Copies of the small scale models used for the beach landings were not adequate.

16. Provisions must be made to bring in a service group with each airborne group landed. Parachute Maintenance recovery crews will have to be included in further operations unless we are to continue our extravagant use of parachutes. Such details must be given no other job than that of recovering and guarding parachutes. Similarly, the glider pilots after their landing has been completed could with a small crew act as guards for the LZs and protect the valuable gliders. In Southern France no guards could be found on the LZs and yet thousands of dollars of expensive instruments were in each glider.

17. A similar recommendation holds true for the air supply dropping. Crew members of the Air Re-Supply units should drop with the bundles to help their immediate recovery. Further, the Air Corps should not attempt to fly in re-supply missions in large unwieldy formation at high altitudes. Such missions require great accuracy if the supplies are to reach the proper personnel on the ground.

1. The recently completed airborne operation “DRAGOON” without doubt was the most successful airborne operation yet undertaken by Allied Forces. (See author’s comments0. The Commanders of both the Airborne and Troop Carrier units are to be highly praised for the excellent manner in which they executed this mission. It is further hoped that the results and experiences of this OPERATION can be transmitted to all Theaters so that even those few mistakes made in this operation will not be repeated again.

1) Take the Airborne Task Force commanded by General Fredricks away from Seventh Army and put it directly under AFHQ for further operations.

2) Request that Mediterranean Allied Air Force (MAAF) commence making arrangements to set up three good airfields as far forward in France as possible which should be held available for the Troop Carrier Command.

3) Put in a bid to SHAEF for one additional Troop Carrier Wing for this Theater, following their next large scale operation up there since at that time they will have Troop Carriers to spare.

4) Send those members of the First Special Service Force (now under ABTF) who are not qualified jumpers to the Airborne Training Center to take the parachute school course so that the Force may be available for the type of operations they were originally set up to handle. It is estimated that all of these men could be qualified in four weeks.

5) That steps be taken to ensure that the 334th QM Depot Co., our American Theater Re-supply organization, be removed from the Seventh Army in time to prevent its coming automatically under SHAEF when that Army (Seventh) goes under SHAEF. If it is thought that this Theater will not require such support for its future commitments, then it is recommended that the unit in question be attached to the VI Army Group.

6) The “pair by pair” system employed in the glider towing was criticized by the glider pilots. They found that after the release had been made, they were often cut out by other gliders as they glided toward their selected touch down point. This, they thought, could be corrected by increasing the distance between the tug teams in column from 1000 to 1500 or 2000 feet. It was further stated that if low angle oblique aerial photos had been blown-up and furnished to the glider pilots for study they could have avoided many of the obstacles which tore up the gliders in landing.

7) That plans be initiated for further airborne operations. Never before have we had such opportunities for continuing operations. We have the troops available, who are well trained and who have just finished a successful mission. Their morale is high, their losses have been low and they are now up to strength having been filled with replacements. Sufficient airfields could readily be made available in Southern France to handle the two or even possibly three Troop Carrier Groups we could use for such operations. By employing our airborne units as regiments and combat teams we could make continuous use of our airborne resources by supporting the advances of both the Seventh and Fifth Armies. Despite the heavy loss of equipment, there are more than enough reserve personnel chutes to permit these operations. With regard to pre-packed supplies we are in an excellent position since less than one-third of the supplies prepared by the Aerial Resupply Company were used in “DRAGOON”.

8) It is further recommended that steps be taken to use the twenty-five light airborne tanks, T9E1, which have just arrived in the Theater. Colonel Heath, Tank Advisor for the VI Army Group has suggested nominating a regular light tank company to work with these tanks. The Hamilcar gliders which are capable of transporting the tanks are available in some quantity in the U.K. By ordering the gliders to this Theater by the first available water transport it is believed that the Airborne Training Center, it could be available for operations within a month. (Sentence is garbled and not clear).

9) It is finally recommended that immediate steps be taken to order 400 CG-4A (Waco) gliders from the United States. There are now but forty of these gliders available in the Theater, 30 of which have been requested by the British 2nd Independent Parachute Brigade Group for operation “Manna”

Sources Used in This Account of DRAGOON

The primary sources for this post-WWII overview of OPERATION DRAGOON came from five principle sources. The Preface and Background sections of this report came from my own personal recollections, teachings, interest and research which have spanned more than twenty-seven years of involvement in the Airborne. The reminder of the material came from the following documents:

1 The 1st Airborne Task Force after action report entitled, “Report on Airborne operations in Dragoon”, dated 25 October, 1944

2 The G-3 Section report on “Airborne operations Dragoon”, dated September 4, 1944

3 “The Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean, 1942-1945, USAF Historical Studies No. 74” prepared by the Military Affairs/Aerospace Historian, Eisenhower Hall, Kansas State university, Manhattan, Kansas, September 1955

4 “Paratroopers Odyssey- A History of the 517th Parachute Combat Team”, published in November 1985.

“The 1st Airborne Task Force Report”, was used almost in its entirety. The Allied Forces Headquarters Report, which was based on the “feeder report’ submitted to higher headquarters by the 1st ABTF was used as a back-up and ‘filler’ until the extracts from the AFHQ Report was used under the “Conclusions’ portion of this overview under the original AFHQ headings of “Conclusions, Summary, and Final Conclusions”. These three AFHQ sections were directly quoted from the final three sections contained in the AFHQ, G-3 Report.

“The Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean 1942-1945, USAF Historical Studies, No. 74”, was used sparingly because of the mass of detail contained in the Report, which was difficult to extract and have fit in with the information contained in the “After Action Reports”. “The Airborne Missions in the Mediterranean, 1942-1945, USAF Historical Studies No. 74” presents an excellent description of the OPERATION and gives a more complete detailed account of OPERATION DRAGOON. It was written some eleven years after the events occurred. “Paratroopers Odyssey- A History of the 517th Parachute Combat Team” was the main basis for the brief account of unit actions and thus the 517th PRCT, the largest of all the troop units participating in DRAGOON, was used for illustrative purposes for the airborne phase of this operation.

Having participated in OPERATION DRAGOON, I felt a certain literary kinship with the source material. The decision to use this material was influenced by my feeling that the 1st Airborne Task Force and the Allied Forces Headquarters After Action Reports were the type of material that should be referred back to for a project of this scope. After all, we who were in DRAGOON knew best how well we performed and operated with respect to our own specific units and to a lesser degree how the other units performed. It would be difficult to give equal time and space to all the units; therefore, a typical unit was selected to illustrate some of the most salient points concerning the amphibious and airborne phase of this operation. Additionally, we, as separate unit associations, have a tendency to become too absorbed in our own piece of the action to the point where we do not have appreciation for the ‘big picture” in terms of how the operation commenced, was executed and ultimately was evaluated. Hopefully this account of the action helps put the operation into larger focus.

I believe that the military tacticians and strategists of WWII as well as most historians of the current era may have lost sight of what DRAGOON offered to this strategy of “combat vertical envelopment”. Some of the most significant lessons of DRAGOON became lost. Foremost among these lessons was the fact that a Theater could put together an Airborne Task Force of Divisional size within such a time frame with a minimum of resources. With additional training, this ABTF was able to launch an airborne assault in coordination with a major amphibious combat landing on and in a completely new Theater of operations.

This type of operation could only be done with inspirational and highly professional leadership at all levels of command. It needed the type of personnel that were indoctrinated with the spirit that whatever needed to be done was done. Everything we did was new and for the most part had never been done before in the annals of modern warfare. They got done because we did not know that these tasks could not be done, we just did them in our own airborne style.

The leadership of the two senior officers directly involved in all phases of this operation was largely responsible for the success of our mission. Major General Robert T. Fredrick, Commanding General of the 1St Airborne Task Force and Major General Paul L. Williams, of the Provisional Troop Carrier Air Division had the ultimate responsibility for the planning, organization, training and conduct of the operation. They and their Staffs and Unit Commanders were the proper mix of professionalism and “daring do”. For some unexplained miracle it all came together at the same time and place to make their mark on the operation.

The 1955 USAF Historical Study no. 74 noted that the highly touted degree of success for the Airborne phase of DRAGOON was considerably less that what was previously announced in the 1944 1st ABTF and AFHQ After Action Reports. The 1955 USAF Historical Studies no. 74 Report had the advantage and knowledge gleaned from eleven years of additional research and study. The fact that DRAGOON was initially announce in 1944 as the most successful airborne operation of its time served a useful purpose at the time, as it encouraged later airborne operations such as ‘Market-Garden” and “Varsity’. The value of repetitive type airborne operations was never really appreciated although the airborne doctrine then as now favored this type of combat operations.

The true value of an Airborne Task Force is in their quickly being ready for targets of opportunity. This is a fact that seems to have been lost on higher headquarters. The Task Force arrangement as used in DRAGOON was an ideal type of configuration wherein specific unattached and detached units could be brought in from the outside and combined for a combat mission with a minimum of time, effort and training, It was a tribute to the state of WWII training and leadership that units like the 602nd Pack Artillery Battalion, the 442nd Regimental anti-Tank Company and the 4.2mm Mortar Chemical Companies could be assembled from a variety of sources and with a minimum of glider training be prepared for combat glider borne operations in such a short time.

It was too bad that some of the recommendations made by Major Patrick D. Mulcahy, Airborne Advisor to the G-3 Section of AFHQ, were not followed up upon. The capability for further airborne operations was intact after DRAGOON, but unfortunately this unique capability was sacrificed by using valuable airborne resources in sustained ground operations on the Franco-Italian border area while guarding that flank of the Seventh Army and the VI Army Group as they advanced to the Rhone River Valley and beyond.

OPERATION DRAGOON illustrated the versatility of airborne forces. It showed how things could be done under adverse circumstances. It proved the value of the Airborne Task Force Concept. It was indeed unfortunate that this gallant force from DRAGOON was broken up and employed separately in conflicts yet to come, such as the Bulge, where these elite units lost their identity and organic resources were transferred to other Airborne units.

The 1st ABTF and its outstanding combat and service units that participated in DRAGOON have every right to consider themselves as a historical legend candidate for the Airborne Hall of Fame.

Colonel Thomas R. Cross U.S.A., Ret.

Atlantic Beach, Florida